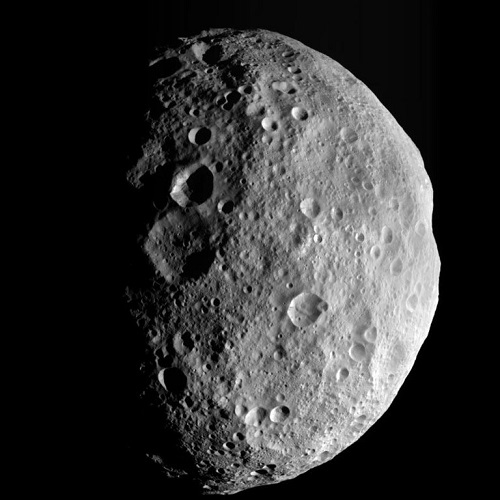

It's incredible to think that pieces of a protoplanet – a large asteroid/small baby planet that never had the chance to become a real one - have been scattered around the solar system and made their way to planet Earth, in our time! And not just that, one piece of the protoplanet Vesta even made it all the way to Belgium. It was seen falling into a barn in the southern village of Tintigny in 1971, by Mr Eudore Schmitz. At the time, it was entrusted to the village teacher for identification, but fell into oblivion for over 40 years. It was only remembered and brought to the attention of scientists in 2017. Shortly after, the children and grandchildren of the Schmitz family donated it to the Museum of Natural Sciences in Brussels, where it still resides today.

We will let you ponder the probability of this event as you read this article, bearing in mind that the solar system is about 4.6 billion years old and there is thus a lot of time for things to happen. Still, of all the pieces of rock from protoplanet VESTA - the second largest asteroid in the solar system and orbiting in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter - that have landed on Earth, in Belgium, within the last century, and have been found... only one exists. To put things in perspective, only nine meteorites of this rare type have been found in Europe.

Meteorites, meteors, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, protoplanets and...?

Agreed, there are many different names to define different types of objects flying around the solar system, and the phenomena that they create on Earth. To explain shortly:

- A meteoroid is a small piece of rock flying in outer space, which can come from a larger asteroid or comet, or has been ejected from a large body like a planet, a moon or a protoplanet.

- When a meteoroid crosses Earth's orbit and is pulled into our atmosphere, it causes so much friction with the molecules of the air that it burns up, either completely or partially. The flash of light that we see as a result and that we often call a shooting or falling star is called a meteor. If part of the original meteoroid survives the burn and lands on the ground, the remaining burnt rock is called a meteorite.

We can detect meteors passing over or around Belgium

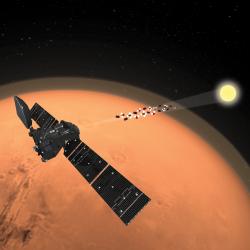

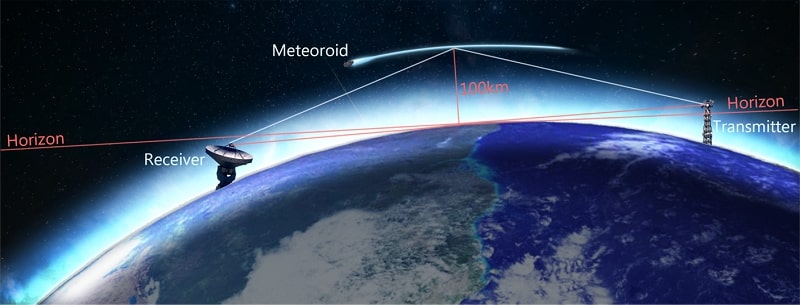

The royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy (BIRA-IASB) has a network of radio receivers spread all over the country, called BRAMS for 'Belgian Radio Meteor Stations'. They are continuously listening to a radio signal emitted towards the sky by a transmitter located in Dourbes. The signal might be reflected by a trail created in the wake of meteoroids passing through the Earth's atmosphere, above Belgium or in the surrounding area. The modification of this signal is recorded, and can be interpreted by our scientists in order to retrieve information about the meteoroid, such as its trajectory, speed or mass/size.

Thus, the data from the BRAMS network, combined with data from other networks, allows us to also determine what might be left of the meteoroid on the ground, as well as the possible location of the meteorite. This is a crucial tool to enable us to find new specimens of meteorites, and allow Belgian scientists to study them.

What stories can meteorites tell us?

Meteorites are a way for the Universe to come to us, instead of having to physically leave planet Earth to go study the Moon, Mars or other bodies. There are only three objects from the solar system of which space probes have brought samples back home: the Moon (a lunar rock can also be seen in the Museum of Natural Sciences), comet Wild 2, and asteroid Itokawa. This means that meteorites are, for the time being, the only specimens of solar system bodies, - other than the Moon, one comet and one asteroid - that we can study in our laboratories on Earth.

Finding out where they come from is a first step. The majority of meteorites on Earth are pieces of rock that have drifted around since the beginning of the Solar System, or pieces that have broken off from asteroids. Occasionally, pieces have been found from protoplanets (but Vesta is the only one of which we are certain to have found meteorites), the Moon and even Mars.

The great majority of all meteorites found on Earth are 'chondrites', rocks that formed in the early solar system and have never come together to form a larger object. They are considered the building blocks of all solar system bodies and have taught us much about it. Five of the six meteorites found in Belgium are of this type (see figure 5 in the left column for their crash dates and locations).

The sixth meteorite is the one from Tintigny. It is an 'achondrite', as opposed to a 'chondrite', and is much rarer than the latter. Furthermore, it has been identified by the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences as a 'polymict eucrite' ejected from the parent body Vesta. The 'eucrite' part of the name is given to a meteorite originating from volcanic activity, and the 'polymict' part means that the rock has undergone collisions when it was still attached to its parent body, creating a specific structure that shows the rock has fragmented and come together multiple times. Only nine objects of this polymict eucrite type were found in Europe to date.

The Tintigny Tale

In conclusion, with the information that science has given us, we can retrace the story of the little Belgian meteorite of Tintigny:

It started its life like all other bodies of the solar system, as dust rotating around a newborn Sun. These tiny particles came together over millions of years, but didn't have the opportunity to become a real planet and just remained a large asteroid. It bumped into other rocks several times, broke apart and came back together.

One day it definitively broke off and journeyed all the way to Earth, got trapped by its gravity, fell and was burned in the Earth's atmosphere in 1971. Only a little piece of the original survived and fell through the roof of a barn in Tintigny. It was finally brought to the attention of the scientific community in 2017, after being forgotten for over 40 years. It was then analysed and identified, and is now publicly displayed for anyone to visit (after the lockdown).

The BRAMS network for the detection of meteors didn't exist back in 1971, but maybe someday, we will be able to find another visitor and discover its secrets!

Radio Meteor Zoo

While we’re all still home for the lockdown - and after that - you can help us detect meteors flying over and around Belgium. Go to the web page of the citizen science project 'Radio Meteor Zoo', and learn all about how to spot a meteor with the BRAMS network - www.radiometeorzoo.be