This is an article from the European Space Agency

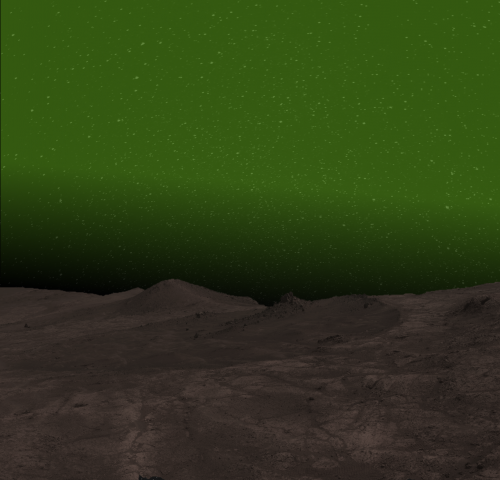

When future astronauts explore Mars’s poles, they will see a green glow lighting up the night sky. For the first time, a visible nightglow has been detected in the martian atmosphere by ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) mission.

Under clear skies, the glow could be bright enough for humans to see by and for rovers to navigate in the dark nights. Nightglow is also observed on Earth, but on Mars it was something expected, yet never observed in visible light until now.

Light the way

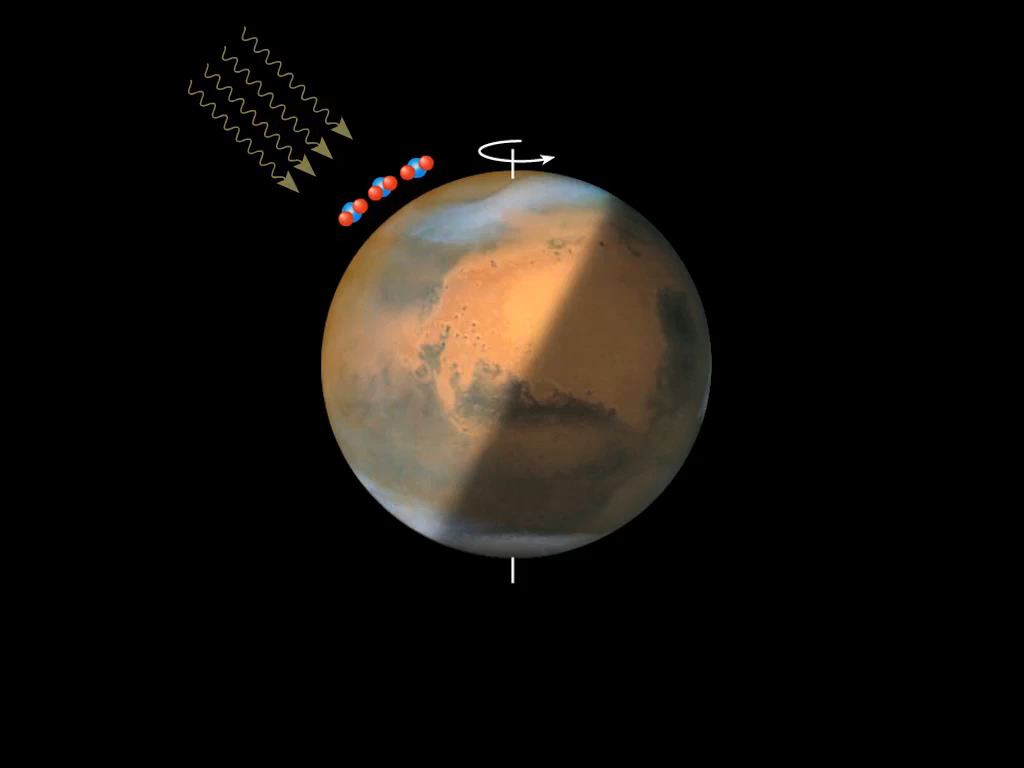

The atmospheric nightglow occurs when two oxygen atoms combine to form an oxygen molecule, about 50 km above the planetary surface.

The oxygen atoms have been on a journey: they form on the dayside when sunlight splits apart carbon dioxide molecules and, when the oxygen atoms move to the night side and stop being excited by the Sun, they regroup and emit light in lower altitudes.

“This emission is due to the recombination of oxygen atoms created in the summer atmosphere and transported by winds to high winter latitudes, at altitudes of 40 to 60 km in the martian atmosphere,” explains Lauriane Soret, researcher from the Laboratory of Atmospheric and Planetary Physics of the University of Liège, in Belgium, and part of the team that published the discovery in Nature Astronomy.

Human explorers could likely see the glow as bright as moonlit clouds on Earth. “These observations are unexpected and interesting for future trips to the Red Planet,” says Jean-Claude Gérard, lead author of the new study and planetary scientist at the University of Liège.

The illumination from the nightglow could be bright enough for future explorers to light the way during the winter polar nights on Mars.

Follow the green glowing road

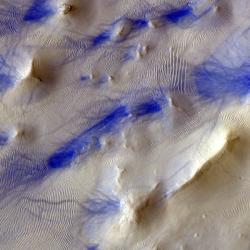

The international scientific team was intrigued by a previous discovery made using Mars Express, which observed the nightglow in infrared wavelengths a decade ago. The Trace Gas Orbiter followed up by detecting glowing green oxygen atoms high above the dayside of Mars in 2020 – the first time that this dayglow emission was seen around a planet other than Earth. These atoms also travel to the nightside and then recombine at lower altitude, resulting in the visible nightglow detected in the new research published today.

Orbiting the Red Planet at an altitude of 400 km, TGO was able to monitor the night side of Mars with its Ultraviolet-visible channel of the NOMAD instrument. The instrument covers a spectral range from near ultraviolet to red light and was oriented towards the edge of the Red Planet to better observe the upper atmosphere.

The NOMAD experiment is led by the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy, assisted by teams from Spain (IAA‐CSIC), Italy (INAF‐IAPS), and the United Kingdom (Open University).

Scientific value

The nightglow serves as a tracer of atmospheric processes. It can provide a wealth of information about the composition and dynamics of an atmosphere, the oxygen density, and reveal how energy is deposited by both the Sun’s light and the solar wind – the stream of charged particles emanating from our star.

The brightness of the emission will also be used to remotely map the oxygen distribution in a region of the atmosphere otherwise inaccessible to other methods

Understanding the properties of Mars’ atmosphere is not only scientifically interesting but it is also key for missions on the Red Planet. Atmospheric density, for example, directly affects the drag experienced by orbiting satellites and by the parachutes used to deliver probes to the martian surface.

Nightglow versus aurora

Nightglow is also observed on Earth, but it is not to be confused with auroras. Aurora is just one way in which planetary atmospheres light up.

Aurorae are produced, on Mars as on Earth, when energetic electrons from the Sun hit the upper atmosphere. They change in space and time, while the nightglow is homogeneous. Nightglow and aurorae can both exhibit a wide range of colours depending on which atmospheric gases are most abundant at different altitudes.

The green nightglow on our planet is quite faint, and so is best seen by looking from an ‘edge on’ perspective – as portrayed in many spectacular images taken by astronauts from the International Space Station.